A Man of Conscience

Photographs of Zalma Tenenberg taken by the SS in 1941. From Państwowe Muzeum Auschwitz-Birkenau w Oświęcimiu, the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum.

Zalma Tenenberg was born in Częstochowa, Poland in 1894. He was the second of eight children of Moszek Lejb and Chaszka Halborn Tenenberg and the uncle of Mojżesz Tenenberg, who's story we have outlined in another post. Here we relate Zalma's story.

Zalma Tenenberg was the son of Chaszka Halborn and Moszek Lejb Tenenberg. He was an uncle or a second or third cousin to many of us who currently identify ourselves as members of the Halborn extended family. His story is not complete. There are fragments to be found here and there: on the Yad Vashem website; in the Piotrków Trybunalski Yizkor book — the book of remembrance about this small Polish town put together by its Holocaust survivors; and in the memoirs and letters of other survivors. The details of those stories often differ. Nevertheless, the story is worth recording — it provides another important chapter in our family history.

In mid-1941, Zalma Tenenberg was arrested in Piotrków Trybunalski along with eleven members of the Judenrat. He arrived in Auschwitz on September 15, 1941. The SS assigned him number 20770, photographed him and interned him as a Jewish criminal.

The SS took mug shots of over 30,000 such supposed criminals. Criminals, according to SS rules, could neither be discharged nor gassed. But they could be hanged or shot or beaten to death.

In January, 1945, as Soviet forces approached Auschwitz, the SS began a forced march of Auschwitz internees toward the west. They also began destroying the mug shots along with the camp’s written records. The mug shot of Zalma Tenenberg survived. If his exact fate was recorded, the record no longer exists. But that he was murdered at some point after his arrival is known.

What was the criminal activity that sent Zalma Tenenberg to Auschwitz a year before the mass deportation and extermination of the Jews began?

Birth Record of Zalma Tenenberg. The record, written in Cyrillic, lists his date of birth as September 22, 1894 in Częstochowa, father Mosziek Lejb Tenenberg, age 33; mother Chaszka Tenenberg nee Halborn, age 33.

Before the War

Zalma Tenenberg was born in Częstochowa in 1894. He was one of eight children born to Mosiek Lejb Tenenberg and Chaszka Halborn. He was one of the numerous grandchildren of Berek Halborn and the even more numerous great grandchildren of our shared ancestors, Ankiel and Chasia Halborn. Alma's family owned a woodworking shop in Częstochowa. The shop produced and sold furniture and employed many family members. Zalma, along with his older brother Berek, worked at the shop from a young age and became skilled carpenters and cabinetmakers.

By the time he was 19, Zalma had taken a leading role in organizing artisans. In 1913, the first legal professional union, a woodworker's union, was organized in Częstochowa and Zalma was elected to the union's first management committee.

Eight years later, in 1921, Zalma's interest in promoting artisan skills and maintaining worker's rights may have been responsible for his move to Piotrków Trybunalski where ORT – the Society for Trades and Agricultural Labor – was establishing a trade school. Zalma worked as an instructor at the ORT school through the 1920s and 1930s.

The Piotrków school was a well regarded part of the community and Tenenberg was a popular and respected teacher. The Piotrków Trybunalski Yizkor (memorial) book, which tells the story of the town before and during the Holocaust notes:

Thanks to the able and dedicated staff, the education and training in the school were of high quality. School director Broide, secretary Leon Kimmelman, instructors Zalman Tenenberg and Joseph Epstein, and teachers Leon Shitenberg and Ms. Rubin worked arduously and efficiently to give the boys the best start in life.

In 1926 Zalma married Klara Herc, who was born in Piotrków Trybunalski in 1903. Their only child, Alexander, was born in Piotrków on May 8, 1937.

Two years after his marriage, Zalma began a political career that was to last until the German invasion of Poland in 1939. In 1928 he was elected to the Piotrków Town council. He was elected again, in 1934, when he was 40 years old.

The 1934 roster of Council candidates, part of which appears below, included his address (#7 Garncarska, which was also the original home of the ORT trade school in Piotrków), profession (school instructor) and level of education (basic). Interestingly, this 1934 roster includes a column marked “wyzn” (an abbreviation for wyznanie, which means religion in Polish). Zalma’s religion is listed on the second page below with the abbreviation “mojz.” meaning the faith of Moses. Other candidates listed — both among those elected and those who were not elected — are listed as “evang.” for Evangelicals or Protestants. Still others are listed with the abbreviation “rz-k” meaning Roman Catholic. Many of those elected at this time, like Zalma, were socialists, either members of the Bund (the Jewish Socialist Party) or of the Polish Socialist Party. Among the others elected were some who belonged to the aggressively anti-semitic National Party. According to some reports from this pre-war decade, disputes between the two factions — socialists and nationalists — were common both in Piotrków Trybunalski and throughout Poland.

During that 1934 election, the Bund slate of candidates (Jewish Socialists) along with the Polish Socialists, received sufficient votes to begin successfully enacting a series of measures that were directed at improving the working conditions and health of Piotrków's underemployed and impoverished workers.

In 1936 Zalma expanded his community activities and, along with other Bund candidates, was elected to the Jewish Community Council of Piotrków. He served as vice president of that council until the time of the German invasion.

Zalma Tenenberg’s name appears on this page of this list of men running for office as members of the Piotrków Town Council in 1934. His address is listed, as is his profession and the abbreviation indicating his religion: “mojz.”, meaning “the religion of Moses”. The last column indicates that Tenenberg was elected.

The First Ghetto

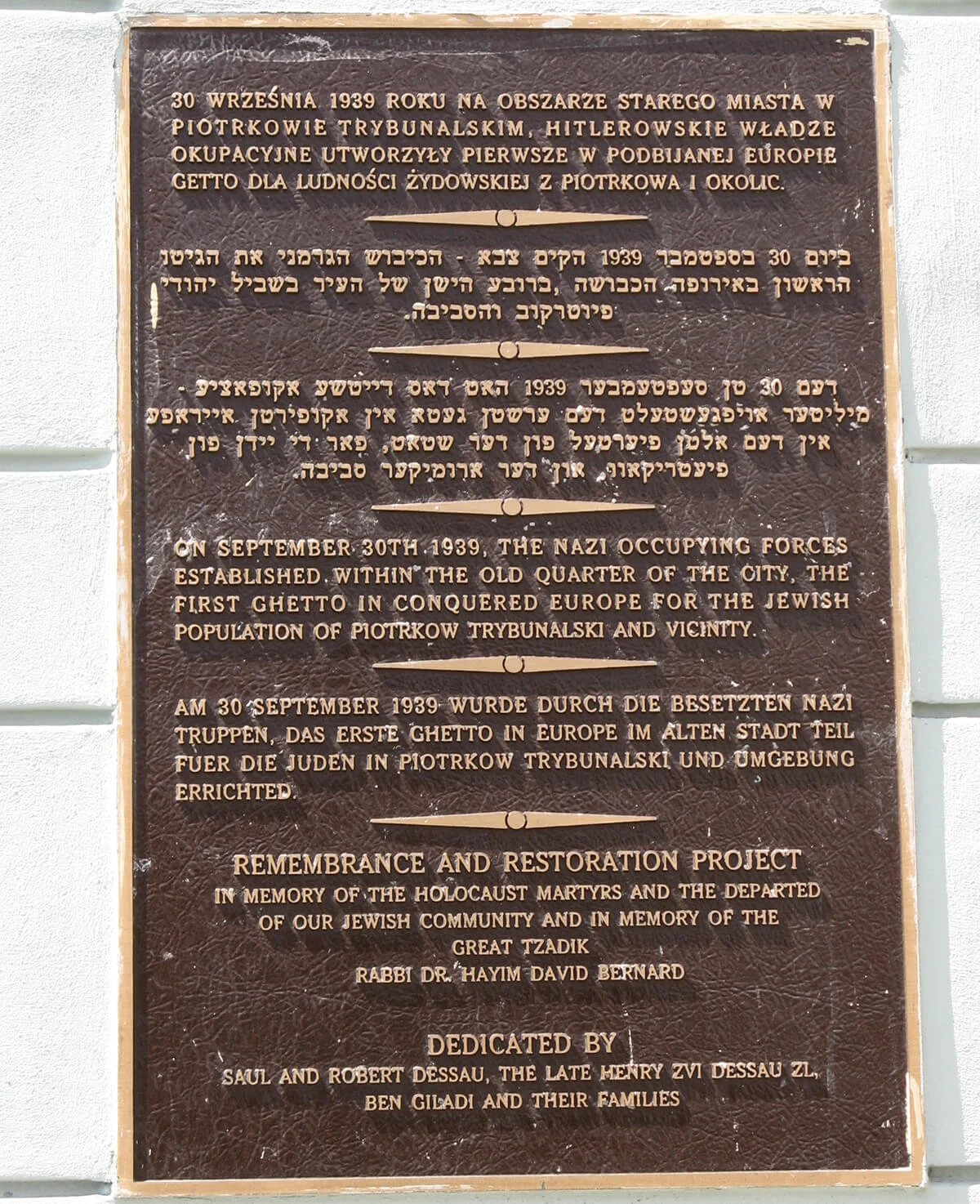

Memorial plaque on the site of the Piotrków Trybunalski Ghetto, the first ghetto ordered by the Germans in occupied Poland.

Zalma and Klara Tenenberg's son Alexander was just two years old when Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939. On September 5 1939, after days of direct bombing that destroyed large parts of the town and drove residents to the countryside, German troops occupied Piotrków. During the first days of German occupation, dozens of Jews were murdered in the town streets, others were captured as slave laborers. Homes and shops were looted and the sale of food to Jews was prohibited. A curfew was imposed closing town streets to Jews except for two hours each day.

About one month later the Germans ordered the creation of a ghetto in Piotrków — the first ghetto in occupied Poland.

On October 14, 1939, Hans Drechsel, the mayor of Piotrków, named Zalma Tenenberg as the first chairman of the Piotrków Trybunalski Judenrat and named Szymon Warszawski as Zalma's deputy. The Judennat started with 12 members, but as more Jews were brought to the ghetto from neighboring villages, the Germans ordered it enlarged to 24 members. The Piotrków Trybunaski Judennat was the first such body created under German rule in Poland. One survivor, Charles Kotkowsky, whose memoirs can be found online at http://migs.concordia.ca wrote:

In October 1939, the Wehrmacht (military) transferred the administration of our city to the civil authorities under the direction of Oberburgermeister Heinz [sic] Drechsel. He did not wait very long with his ordinances. He set up the Jewish Council (Judenrat) to carry out his instructions. Some members of the Council thought that they would run the affairs of the ghetto in the pre-war tradition of Jewish self-government.

They were misled, deceived. Drechsel ordered the former vice president of the Jewish Council Zalman Tenenberg to form a Judenrat. Tenenberg was a member of the Jewish socialist Bund organization. He was short, slim, athletic and had a strong character. He surrounded himself with twenty-three co-workers, mostly his party members, some of whom had served on the Council before the war.

On October 8, 1939, Drechsel ordered that the 16,000 Jews, including refugees from other towns, who lived throughout the city, move into a crowded section. He wanted to accomplish this task within a few days. It was humanly impossible. It took a lot more time to shift people around, and Piotrków became the first ghetto in occupied Poland.

At the end of the 1930s Piotrków Trybunalski had, at most, about 50,000 residents. The Jewish population before the occupation has been estimated at between 10,000 and 12,000. Another 6,500 town residents, including the man who served as mayor of the town under the occupiers were German Volksdeutsche. And for the mayor, as for most Volksdeutsche, collaboration with the German occupiers was both natural and profitable.

As the exchange of housing took place, in a pattern that later became familiar as other ghettos were ordered into existence, Volksdeutsche took the lead in moving into newly vacated Jewish homes and quickly acquired deserted Jewish businesses. The ghetto area selected by the Germans was small. Prior to the war, the area, now by German order to house about 16,000 Jews, had housed between 5,000 and 6,000 people.

The purpose of the Judenrat was not to debate, decide and manage the affairs of the Jewish community and not to facilitate cooperation with the authorities. In the eyes of the German invaders, the purpose was solely to act as an instrument to implement and enforce German orders.

Zalma Tenenberg seems to have understood this from the beginning. But the objectives he and his colleagues set for themselves were not the same. Instead, they set out first, to use whatever small freedom of movement their Judenrat appointments provided to cope with the growing needs of ghetto occupants and second, to organize an active resistance movement, in cooperation with the resistance movement throughout Poland.

During the early months of the ghetto they met with some very limited success in achieving the first of these goals: in coping with community needs.

According to Yad Vashem, “Until October 1940 the Judenrat succeeded in helping a number of Jewish families in the ghetto to emigrate from Poland.”

But the ghetto continued to grow. The Yad Vashem article on the Piotrków ghetto continues:

…the number of residents in the ghetto continued to rise steadily, due to an influx of Jewish refugees. While at the beginning of the war the city had held some 10,000 Jews, by April 1942 the number had risen to 18,500. All the Jews now lived within the ghetto, and nearly 8,000 of them were refugees. The refugees came primarily from areas in western Poland – Pomerania, Poznańn and Łódź – which had been annexed to the German Reich. Additional refugees came from Polish territories which had been annexed to the Soviet Union; these were refugees who had fled when the Soviet Union began deporting Jews to Siberia.

Under Tenenberg’s leadership, in the early months of the ghetto, the Judenrat found housing for the newcomers in the already overcrowded ghetto, distributed money to the needy, established an orphanage and a children’s club, and organized public kitchens, two clinics, a pharmacy, a dental office and a family health center. The Judenrat also organized workshops to provide goods to the Germans and income to ghetto residents.

As forced labor rapidly became mandatory for more and more people interned in the ghetto Tenenberg tried to provide documents for those who could not work and could not pay the bribes necessary to avoid such work. One such document (below) titled “Certificate” and dated 9 January, 1940, just two months after the ghetto was ordered by German authorities, reads, in part: "The Council of Elders of the Jewish community in Petrikau hereby certifies that Anszel Nyss, living in Petrikau, Garncarskastrasse 13, since April 1939 is paralyzed and therefore cannot work. . . he has no savings and no sources of income. He also has a wife and two children ages 4 and 10 years."

In the beginning of December 1939, Drechsel, the mayor of the city, known as a vicious anti-Semite, summoned Chairman Tenenberg to his office and ordered that the Jews of Piotrków construct military barracks.

The construction materials were extremely costly and this levy was imposed after three contributions had already been extracted from the Jewish community. Tenenberg manifested great courage by categorically refusing to have the Jews pay the contribution. Drechsel began to threaten. Tenenberg told the mayor that he could shoot him if he liked, but the Jews would not give the money and he left the room. The next morning, an urgent meeting of the Judenrat was convened to discuss the question. During the meeting an emissary from the mayor's office arrived for Tenenberg to see the mayor at once.

The mayor informed Chairman Tenenberg that he was releasing the Jews from the obligation of covering the cost of the construction materials for the barracks.

On another occasion, during the early days of the ghetto, Tenenberg was even able to relieve the grim reality of ghetto life for one evening. Ben Giladi, in his contribution to the Piotrków Yizkor book, wrote:

In 1940, during one of the “breathing spells” in the ghetto when the Nazis weren't pushing so hard, the teachers, with the help of Zalman Tenenberg, the first chairman of the Judenrat (deported later to Auschwitz for illegal activities), organized a “Kiermasz” (bazaar). The artistic evening took place at the Joseph Hertz auditorium and the proceeds were designated for “Winterhelp.” The event was one of the brightest spots in our burdened lives. The auditorium was decorated as during the good old school days before the war. The artistic part was unforgettable. I still remember my fellow students: Ada Makowska reciting Bialik in Hebrew; Szymek Librach reciting “Piotr Plaksin” and “Dancing Socrates” of Tuwim; Edzia Orbach doing a sketch. A dramatization of Antski's “Day and Night” with songs and dances was also presented. Ala Braun did pantomime. Zosia and Jakubek Bomstein played the piano. The people were thrilled and the true value of education suddenly emerged. Alas! This was the only major artistic event in the ghetto. Awful times zeroed in closely and inevitably upon the community.

These small victories were few and far between.

In The Holocaust: The Fate of European Jewry, 1932 - 1945, Leni Yahil writes of “the efforts of the Judenrat at Piotrków Trybunalski to preserve Jewish life and to care for the numerous refugees who reached the town.” Those efforts, however, are described by Yahil as “the Piotrków Trybunalski illusion.”

By mid-1940, less than a year after the Jews of Piotrków where forced into a ghetto, the community resources were decimated. In August 1940, the Judenrat received a communication from the Jewish mutual aid organization of Kraków, asking for a list of self help organizations available in the Piotrków Jewish community. The Jews of Kraków, at this time, had not yet been forced into a ghetto, though they already suffered a wide range of abuses. The query appears to have been aimed at ascertaining what self help resources the Piotrków community had and whether or not they had been registered with the Government General — the German administration that controlled Polish territories that had not been incorporated into the Greater Reich. Tenenberg wrote:

We have thoroughly analyzed the broad composition and the assets of associations dissolved by virtue of Governor General ordinance issued on July 23 but due to the absence in General Government of many people engaged in these associations activities we were unable to get the full information.

The details supplied in Tenenberg’s late August 1940 answer were grim— the major charitable institutions of the Piotrków Jewish community had been stripped of their assets and the institutions and their personnel were all but non-existent. The ORT society — the local organization that had, before the war, run the trade and agricultural school where Tenenberg had been employed was no longer active. “Some machines were previously taken away,” Tenenberg wrote, and “currently refugees are living there, lodged by the Jewish community . . . The society that had run a care station for mothers and children is not working . . . Some of the assets are located at St. Trinity Hospital where they were taken when the Jewish Hospital was closed.” And the Benevolent Society for Children, which ran the Jewish community orphanage “is not working . . .” Tenenberg reported that despite the disappearance of the society ‘the orphanage still exists.” In other words, the community still had orphans and the Judenrat was attempting to house them, although the self help organization that had cared for orphans before the war no longer existed.

Other charitable institutions still existed, Tenenberg wrote, but apparently in name only. . . “their property does not belong to us and in fact does not exist.”

Tenenberg went on to state that the three major self help groups — the societies that supported the ORT trade school, the care station for mothers and children and the orphanage — were “an absolute priority for the Jews of Piotrków.” He then pleaded that the Kraków self help group “defend these societies with the [Government General] authorities.”

He concluded with a plea for help in re-establishing the Piotrków Jewish hospital, which had been “in its entirety with its equipment incorporated into the Public Hospital St. Trinity,” and thus was no longer available to the Jewish community. “The Jewish hospital,” he wrote, “was not a property of any society — it was a Jewish foundation for hospital treatment of Jews. The restitution of this hospital to the Jewish community is, in our opinion, absolutely necessary and essential to the Jewish community.”

But the Kraków Jewish community was in no position to help. By May, 1940, all but 15,000 of the 65,000 Kraków Jews had already been deported or killed. And six months later, in March, 1941, the remaining Jews in Kraków were crammed into another ghetto, in the Podgorze district of the city.

Even the effort to alleviate starvation was becoming a loosing one. In late November 1940 Tenenberg wrote an urgent message to the Jewish self help organization in Kraków, informing them that, despite a circular announcing the availability of potatoes, no order had been issues allowing the self help organization in Piotrków to buy them for the Jewish population. Nor did the community have any money available to buy potatoes or any other vegetables at affordable prices either with or without official approval. Almost exactly a year after the Jews of Piotrków were ordered into a controlled, small ghetto, neither the Jewish self help organization nor the Judenrat was able to feed the population.

Tenenberg's November 28, 1940 communication to the Jewish self help organization in Kraków. Tenenberg states that, while the Polish community had received authorization to buy potatoes for the Polish population, no such authorization had been issued for the Jewish population. He goes on to state that, even if food was available, the Jewish community had already been stripped of cash enough to purchase it.

Arrest and Murder

For a while, the Piotrków Judenrat was able to pursue Tenenberg’s second major goal— the creation of a resistance movement within the ghetto and participation in the wider resistance movement in Poland. Communication lines were established with Polish resistance organizations in other towns and cities. But less than two years after the Germans ordered the creation of the ghetto, it was this goal that led to the arrest and imprisonment of Zalma Tenenberg and his associates.

The Piotrków Yizkor book gives the following account of the arrest of Tenenberg and other members of the Judenrat in mid 1941:

In July, 1941, a Polish underground courier, Maria Szczesna, was arrested by the Gestapo while carrying illegal publications and the names of most of the Council as underground activists. The Germans learned who was involved in the resistance and rescue endeavors. Shortly thereafter, a few of the Council members were arrested, among them chairman Zalman Tenenberg, treasurer Zalman (Stach) Staszewski, Maierowicz, Fraint and others. One of them, Jacob Berliner, surrendered to the Germans of his own will in solidarity with the arrested colleagues. They were sent to Auschwitz, and, shortly afterward, a telegram arrived stating that they all had died.

In the Yad Vashem account of Piotrków Trybunalski during the Holocaust, the story of the arrest is similar:

In the second half of 1941 the ghetto was more stringently isolated and the persecution of the Jews increased. In July of 1941 a number of Judenrat members were arrested, including the chairman, Zalman Dannenberg [sic], together with a number of the ghetto’s administrative staff, and members of the Bund. In September some of them were deported from Piotrków Trybunalski and apparently murdered following the discovery of their underground activities.

Another account of the arrests, from the HolocaustResearchProject.org is more specific:

Between June and July 1941, the Germans uncovered the existence of a Jewish underground movement in the ghetto, eleven members of the Judenrat, which had been cooperating with the underground were arrested, amongst this number was the President Zalman Tennen[berg].

On September 13, 1941, after more than two months of interrogation and torture, all of those arrested were sent to the Auschwitz concentration camp. A few days later, the families of those taken to Auschwitz were informed of their deaths “due to illness.”

Zalma Tenenberg left no direct descendants — his wife, Klara, and his son, Alexander were sent to Ravensbruck several years after his arrests. In early 1945 as the Russians advanced into Germany they were transferred west to Bergen-Belsen. There is a record of their names in the Bergen-Belsen Book of Remembrance. It lists the date of their deaths at Bergen-Belsen only as 1945. British troops liberated Bergen-Belsen on April 15, 1945. We do not know if Klara and Alexander perished before or after the British arrived.

Memorial headstone in the Piotrków Trybunaski Jewish Cemetery. The headstone is dedicated to Jewish Bund members who took part in the resistance during World War II. Zalma Tenenberg's name is the second in the left hand column of the bottom photograph. The photos were taken from Gidonim.com, and are reproduced here courtesy of the Gidonim project, which every year sends graduates and teachers from the Re'ut School in Jerusalem to renovate Jewish cemeteries in Poland.